Saturday, February 17 marks the 209th anniversary of the day that the Treaty of Peace and Amity reached President James Madison at The Octagon and was signed in what is known today as the “Treaty Room”.

This treaty ended the War of 1812, fought between Great Britain and the fledgling United States. The war had caused great destruction in the young nation’s newly established capital. In 1814, British troops burned federal buildings, including the White House and the United States Capitol. After the burning of the White House, President James Madison and First Lady Dolley Madison moved into The Octagon House, the nearby Washington home of their acquaintances John and Ann Tayloe, for a period of six months, from September 1814 to March 1815.

The purpose of the treaty was to achieve “universal Peace between His Britannic Majesty and the United States.” Prisoners of war were to be returned; both sides agreed to seek peaceful relations with the Indians; and efforts would be made to end the slave trade,” according to Hugh Howard’s Mr. and Mrs. Madison’s War: America’s First Couple and the Second War of Independence.

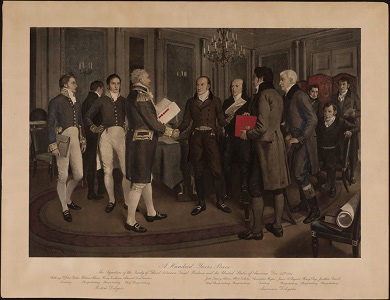

Three different copies of the treaty were sent from Ghent, Belgium, where negotiations took place, to Washington, D.C., in case one shipment was delayed or lost. After reaching the United States Congress, the treaty was delivered to The Octagon by Henry Caroll, secretary to Congressman Henry Clay. “Madison walked into his study, an exquisite wood-paneled circular room over the entrance hall. He crossed the pine floor and sat down before a delicate mahogany desk; its round top covered by dark green leather stamped with gold. With characteristic precision and formality, Madison put his signature to the “Treaty of Peace and Amity,” Howard said.

The ceremony took place in the “President’s office in the circular room on the second floor over the entrance of the Octogen,” according to historian, Audrey Cutler.

Servants yelled down the stairs to bring the champagne, and Paul Jennings played “The President’s March” on his fiddle.

In his Reminiscences, Jennings writes that “we were crazy with joy.” The butler liberally dispensed wine to all, including the servants and slaves… [Sioussat] and some others were drunk for two days, and such another joyful time was never seen in Washington.”’

According to Joseph Gale, an eyewitness, “Soon after nightfall, Members of Congress and others deeply interested in the event, presented themselves at the president’s house, the doors of which stood open. When the writer of this entered the drawing room at about eight o’clock, it was crowded to its full capacity, Mrs. Madison (the president being with Cabinet) doing the honors of the honors of the occasion. And what a happy scene it was.”

Candles were later burned in The Octagon’s windows celebrating the end of the War of 1812 and Madison’s exemplary leadership.

REFERENCES

Cutler, Audrey. “A Synopsis of Events of the War of 1812 and its Relationship to the History of the Octagon”

From the Octagon Files. “Interpreter’s Insights: Presidential History and Legends at the Octagon”

Green, Contance McLaughlin. “Washington Village and Capital, 1800-1878.

Howard, Hugh. Mr. and Mrs. Madison’s War: America’s First Couple and the Second War of Independence. Bloomsbury Press, 2012

Hunt-Jones, Conover. “Doly and the ‘Great little Madison.’” AIA Foundation, 1977

Jennings, Paul. A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison. Cornell University Library, 1865.

Lord, Walker. The Dawn’s Early light, New York, 1972.

Miller, Hope Riding. “Great Houses of Washington.”

Taylor, Contributor: Elizabeth Dowling. “Paul Jennings (1799–1874).” Encyclopedia Virginia, 2 Dec. 2021, encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/jennings-paul-1799-1874/.