Written by AF Staff, Research by Kayla Laws

During Black History Month, the Octagon Museum would like to remember the names of the formally enslaved who worked in the house:

LAND RECORD (From the Octagon Museum Files)

Certificate of Slave:

December 22, 1817

John Tayloe III

Cert. of Slave

I hereby certify that I brought from the state of Virginia to the city of Washington the following slaves: Archy, Harry, John, Lewis, Betty, Henry, Winny, Maria, Sinah, Kitty, Godfrey, George, Travis, Horace, John, and Winny which I have brought for my use. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this 22nd Day of December A.D. 1817.

John Tayloe (sealed).

About ten enslaved people lived in The Octagon year-round. Most of them traveled back and forth between DC and the Mt. Airy plantation with the Tayloes, so when they were present, its enslaved population was likely around 18-20 enslaved people.

One of the former enslaved, Archy Nash, was put in John Tayloe III’s will, text from which is retrieved from the White House Historical Association:

“I will that my body servant Archy may be liberated and may be allowed one hundred dollars per annum during his life. My motive for liberating him is his long-tried fidelity, especially since I have been in bad health, & upon one occasion, he was the means under the direction of providence, of saving my life.”

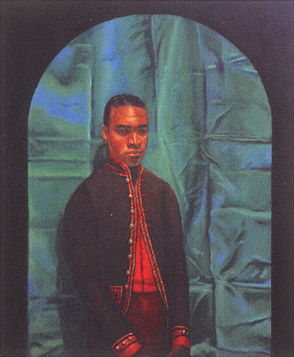

Figure 1: “Archy Waiting,” by Peter Waddell Facets and Reflections: Painting the Octagon’s History – Peter Waddell.

Archy Nash was John Tayloe III’s “manservant” and would have slept on the second floor landing outside of the master bedroom.

Ann Tayloe’s lady’s maid was Winney Jackson. She would have also slept outside the master bedroom, like Archy. If Ann or John needed something at 3am, Archy and Winney had to be there to get it for them. “At night they would retire to the servants’ hall or outbuildings in the yard; personal attendants to the Tayloe’s like Archy, Winney, and Betty probably slept close to the family rooms in case they were needed during the night, sometimes on mattresses placed just outside the family’s bedroom doors,” according to Julianna Jackson, historical archeologist for the White House Historical Association.

According to Richard Dunn, author of “Winney Grimshaw, a Virginia Slave, and Her Family,” “Subversive interracial sex cuts like a knife through Winney’s story. She was manipulated to an extraordinary degree. And her family was deliberately torn apart. She had to cope with continual exploitation by her white masters—and cope she did. The last reference to her that I can find comes from her former owner, William Henry Tayloe. Reminiscing about his experiences as a slaveholder in 1868, Tayloe remarked that ‘Winney Grimshaw could fill a volume with interesting events, if she could write.’ If she could write . . .”

Harry Jackson, Gowen, and Henry Jackson worked with Tayloe’s prized horses as coachmen and stable workers. “The Octagon boasted its own stable complex, located in the rear of the house on the west side of the lot, with stalls for carriage horses on one side and saddle horses on the other,” Jackson said.

The Tayloes also relied on enslaved domestic servants like Lizza, Peter, and John, who were butlers. All these people navigated the concealed service spaces as part of their daily work.

A painting by artist Peter Waddell, currently displayed in the drawing room of The Octagon, depicts an enslaved man, possibly Peter or Archy, standing with his back to the viewer in the foreground.

Figure 2: “An Evening Party,” by Peter Waddell.

According to John Tayloe’s records, Peter was sold in 1816 for unspecified “misbehavior.” “We know that John preferred not to use corporal punishment on the enslaved people, instead relying on more psychological punishments,” according to Octagon archival records on Peter. Enslaved people like Peter were sometimes sold, often away from their families, in retaliation for things like attempting to run away.

In terms of how the enslaved navigated the house, there was a stairwell for servants and the enslaved. The service stairs were hidden from the rest of the house by doors designed to blend into the surrounding walls. “People like Winney, Betty, Archy, and Lizza would have had to trek up and down the narrow service stairs countless times a day, at the beck and call of the bell, giving the impression that meals and service appeared almost by magic,” according to Jackson.

Figure 3: “Servants Stairs.” From Octagon Files.

In the Octagon’s basement, there is a servants’ hall. It served as a “gathering space for the slaves,” according to Amanda Ferrario, Manager at the Octagon Museum. They would have taken their meals there and performed chores such as cleaning knives, polishing candlesticks, removing spots from linens, etc. There also was a call-bell system that would have connected to the servants’ hall. “The servants’ hall was a common room for day and evening use where meals were served, simple chores completed, and idle conversation exchanged while awaiting a summons from upstairs,” Orlando Ridout said.

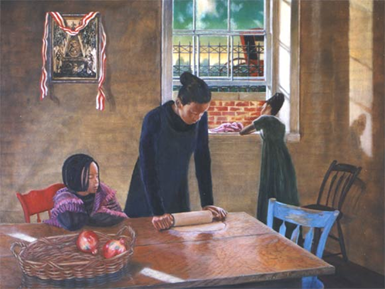

Figure 4: “Kitchen Work,” by Peter Waddell. Facets and Reflections: Painting the Octagon’s History – Peter Waddell.

Billy was the cook for Tayloes at the Octagon. He “likely kept busy in the basement kitchen preparing dishes for the Tayloe’s table,” Jackson said.

Figure 5: “Kitchen in the Basement of the Octagon House.” From Octagon Files.

“The design of the Octagon takes great pains to hide the incredible amount of work that was done behind the scenes by enslaved people,” according to the Octagon archival files on Peter.

In terms of the social aspect between the enslaved, there was little to none. According to Laura Croghan Kamoie, author of Between Two Worlds, the 1820 Washington Directory indicates that “not many other slaves lived near the Octagon, making it difficult for the Tayloe slaves to form relationships.” There were also markets where the enslaved were asked to purchase goods and services. One market, the “President’s Square Market was within walking distance of The Octagon and was one of the best opportunities for slaves to socialize with other blacks,” Kamoie said.

Something important to note is that “the Octagon House had an enslaved labor force that was much higher than the national average. All are exceptional properties in that they were built by men of great wealth in a style that was far superior to the most common dwellings of the period,” according to Jackson.

Even though the archive of the enslaved at The Octagon is incomplete, passages found in wills, newspapers, and account books are usually the beginning stories of the enslaved people. How we find the names of enslaved people such as Archy Nash, Winney Jackson, Harry Jackson, and Billy is how we can remember them and hopefully research more about their lives.

The Octagon currently has an exhibit titled I Was Here. As you walk through the house, you will notice tapestries hung in the windows. These ancestor spirit portraits serve as a reminder of those individuals who lived and worked at The Octagon.

The I Was Here project began by photographing contemporary African Americans as archetypical Ancestor Spirits that embody the Human Family: mother, father, brother, sister. The portraits from cohesive, ethereal images convey the dignity of the African American individual and family where most were separated due to “misbehavior” according to the Tayloe Family. Family separation was a “common experience…where girls and boys were typically moved away from their parents in the early to mid-teens, when they were old enough to start regular jobs,” according to Dunn.

Figure 6: I Was Here Tapestry currently displayed at the Octagon Museum. From Octagon Files.

The project invites visitors to allow this During Black History Month the Octagon Museum would like to remember the names of the formally enslaved who worked in the house:

References

Dunn, Richard S. “Winney Grimshaw, a Virginia Slave, and Her Family.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 9 no. 3, 2011, p. 493-521. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2011.0029.

Ferrario, Amanda. “Basic Guided Tour of the Octagon Museum.” From Octagon Museum Files, 2022.

Jackson, Julianna G. “Slavery at the Octagon.” WHHA (En-US), Whitehousehistory.org/slavery-at-the-octagon.

Jackson, Julianna G “The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia.” William and Mary Press, 2017.

Ridout, Orlando. Building the Octagon. American Institute of Architects Press, 1989.